Abstract Link to heading

Geospatio-temporal data are pervasive across numerous application domains. These rich datasets can be harnessed to predict extreme events such as disease outbreaks, flooding, crime spikes, etc.

Statistical methods based on extreme value theory provide a systematic way for modeling the distribution of extreme values. In particular, the generalized Pareto distribution (GPD) is useful for modeling the distribution of excess values above a certain threshold. However, applying such methods to large-scale spatio-temporal data is a challenge due to the difficulty in capturing the complex spatial relationships between extreme events at multiple locations.

This paper presents a deep learning framework for long-term prediction of the distribution of extreme values at different locations.

Introduction Link to heading

Given the severity of their impact, accurate modeling of extreme events are therefore critical to provide timely information to the public threatened and to minimize the risk for human casualties and property destruction.

Numerous methods have been developed in the past for modeling extremes. This includes outlier detection methods where the goal is not to predict future extreme events but to detect them retrospectively from observation data after they have occurred.

Statistical approaches based on extreme value are also commonly used to infer the statistical distribution of the extreme values. Another approach is to cast the prediction of extreme events as a supervised learning problem.

we are interested in predicting the conditional distribution of excesses over a threshold (e.g., monthly precipitation or temperature that exceeds their 95th percentile) at various spatial locations. However, predicting the conditional distribution of such excesses is a challenging problem due to their rare frequency of occurrence. In addition, the predictive model must consider the complex spatial relationships between events at multiple locations.

Identifying such complex and potentially nonlinear interactions among the predictors is a challenge that must be addressed.

Non-parametric deep learning methods are generally ineffective at inferring the distribution of extreme events unless there are sufficiently long, historical observation data available. When trained for regression problems, deep learning models are generally trained to predict the conditional mean of a distribution using the mean squared error loss, and thus, fail to capture the tail of the distribution.

Extreme events are governed by two parametric distributions: the distribution of block maxima is governed by the generalized extreme value distribution (GEV) and the distribution of excesses over a threshold are governed by the generalized Pareto distribution (GPD).

The authors propose a novel framework that combines extreme value theory (EVT) with deep learning. Specifically, the framework leverages the strengths of deep learning in modeling complex relationships in geospatio-temporal data as well as the ability of GPD to capture the distribution of excess values with limited observations.

However, integrating a deep neural network (DNN) with EVT is a challenge as the loss function minimized by the DNN must be modified to maximize the likelihood function of the GPD.

Another computational challenge is that the sufficient statistics of GPD must satisfy certain positiv- ity constraints unlike the output of DNN, which are typically unconstrained.

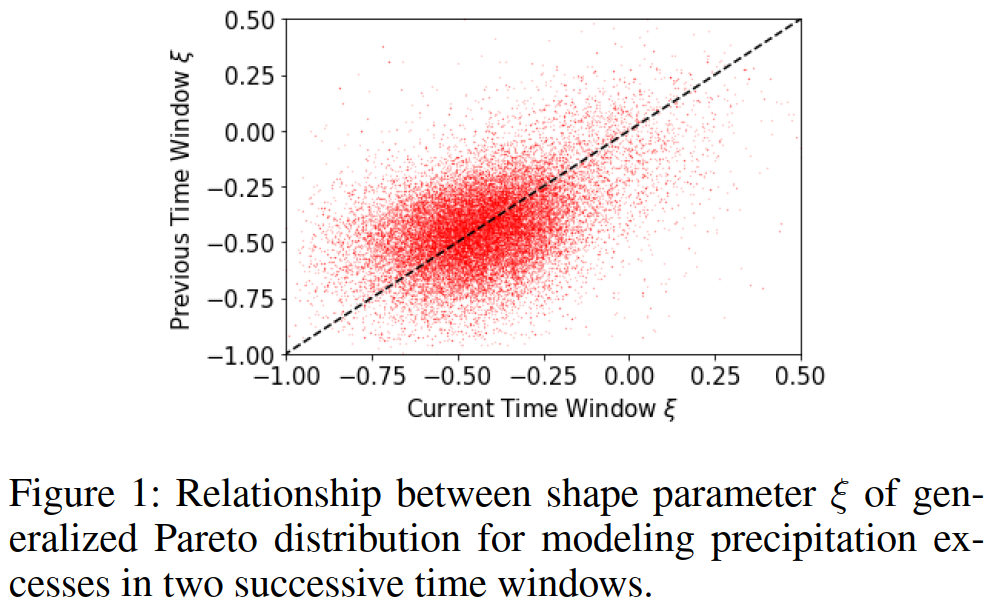

Further, the distribution of extreme values are often temporally correlated. This poses a challenge from a modeling perspective as the number of excesses above a threshold tends to vary from one time step to the next.

The major contributions of this paper:

-

A deep learning framework to model the distribution of extreme events. The framework combines CNN with deep sets for modeling geo-spatial relationships among predictors that include fixed-length vectors and variable-sized sets.

-

A re-parameterization method for constraining the outputs of the DNN so that they satisfy the requisite constraints and present an algorithm that learns the GPD parameters in an end-to-end fashion.

-

Evaluate the proposed framework on a real world climate dataset and demonstrate its effectiveness in comparison to conventional EVT and deep learning approaches.

Related Work Link to heading

The strength of CNN lies in its ability to model spatial relationships. For example, CNN has been success- fully used to model spatial relationships in geographic applications. There have also been concerted efforts to model both spatial and temporal relationships jointly using CNN. Instead of applying convolution to model temporal relationships, some research uses recurrent layers to model temporal relationships. However, none of these approaches are designed for modeling extreme values.

Statistical approaches based on extreme value theory (EVT) are commonly used to infer the distribution of extreme values. Several recent papers have combined deep learning with EVT but often only as a post-processing step. In none of these cases are deep learning and EVT integrated together within a single end-to-end learning framework. Instead, EVT is used as a post-processing step to identify unusual samples or as a robustness score of the network. In contrast, the authors integrate EVT directly into our deep learning formulation to predict the GPD parameters and training it in an end-to-end fashion.

Preliminaries Link to heading

Let

$$\mathcal{D}=\left\{(X_{il},Y_{il})|i=\in\{1,\cdots,n\}; l\in\{1,\cdot,L\}\right\}$$be a geospatio-temporal dataset, where $X_{il}$ denote the predictor attribute values for the time window $(t_{i-1},t_i]$ in location $l$ and $Y_{il}$ denote the corresponding target (response) values for the time window $(t_i,\dot t_{i+1}]$ Since we are interested in predicting the excesses above a threshold in the next time window, the target variable corresponds to the set of excess values at location $l$ during the period $(t_i,t_{i+1}]$, i.e.,

$$Y_{il}=\{y_{tl}\mid y_{tl}\geq u,t\in(t_i,t_{i+1}]\}.$$In addition, the predictors can be divided into two groups, $X_{il}\equiv(X_{il}^v,X_{il}^s)$, where $X_{il}^v\in\mathbb{R}^d$ is a fixed length vector and $X_il^s\in\mathbb{R}^{p_i}$ is a variable length vector corresponding to the set of excess values in the previous window, i. e. ,

$$X_{il}^{s}= \{ y_{tl}\mid y_{tl}\geq u, t\in ( t_{i- 1}, t_{i}] \} .$$Note that the number of excess values can vary, e.g., one window may have $10$ excess values while the previous window has only $5$ excess values. The collections of excess values associated with the current and next time windows form the sets $X_{il}^s$ and $Y_{il}$, respectively. Our goal is to estimate the conditional distribution $P(Y_{il,j}|X_{il})$ for all the locations $l_{i}$ conditioned on the predictors observed in the current window, where $Y_{il,j}$ is an element of the set $Y_{il}$.

Extreme Value Theory Link to heading

This paper focuses primarily on the use of generalized Pareto distribution (GPD) for modeling the distribution of excesses above a given threshold. For example, in precipitation prediction, one may be interested in modeling the distribution of high precipitation values above a certain threshold.

Let $Y_{1}, Y_{2}, \cdots$ be a sequence of independent and identically distributed random variables. Given an excess value $Y=u+y$, where $u$ is some pre-defined threshold, the conditional probability of observing the excess event is:

$$ P(Y-u \leq y \mid Y>u)= \begin{cases}1-\left[1+\frac{\xi y}{\sigma}\right]^{-1 / \xi}, & \xi \neq 0 \\ 1-e^{-y}, & \xi=0\end{cases} $$Furthermore, its density function is given by:

$$ P(y)= \begin{cases}\frac{1}{\sigma}\left[1+\frac{\xi y}{\sigma}\right]^{-\frac{1}{\xi}-1}, & \xi \neq 0 \tag{1}\\ \frac{1}{\sigma} e^{-\frac{y}{\sigma}} & \xi=0\end{cases} $$subject to the constraint $\forall y: 1+\frac{\xi y}{\sigma}>0$. The GPD has two parameters, shape, $\xi$, and scale, $\sigma$ The shape parameter has a significant impact on the overall structure of the probability density. When $\xi$ is negative, the support of the distribution is finite such that $0<y<-\frac{\sigma}{\xi}$ due to the constraint. When $\xi$ is zero or positive, its support ranges from 0 to positive infinity.

The advantage of using the GPD to model extreme values is its generality as one does not have to know the underlying distribution of the random variable prior to thresholding since the distribution of excesses will be governed by the GPD in relatively general conditions.

In many cases, the values of $\xi$ and $\sigma$ may depend on some contextual features as predictors $x$. Assuming a linear relationship between $\xi$ and $x$ and between $\log (\sigma)$ and $x$ (the log linear relationship is used to guarantee that the estimate of $\sigma$ is non-negative)

$$ \xi=f_{\xi}(x)=w_{1}^{T} x, \quad \log (\sigma)=f_{\sigma}(x)=w_{2}^{T} x \tag{2} $$where $w_{1}$ and $w_{1}$ are the model parameters, which can be learned by minimizing the negative log-likelihood of GPD.

One important consideration when modeling data using a GPD is the choice of threshold $u$ since the threshold must be set high enough for the GPD to be applicable. A common way to evaluate the suitability of a given threshold is by examining the mean residual life plot. If a collection of samples were drawn from a GPD then the empirical distribution of the excesses should have a linear relationship with selected threshold. Specifically, we have:

$$ \begin{equation*} E(Y-u \mid Y>u)=\frac{\sigma_{0}+\xi u}{1-\xi} \tag{3} \end{equation*} $$for threshold $u$, and $Y \sim G P D\left(\xi, \sigma_{0}\right)$. In the experiment section, we will verify our choice of threshold by examining the mean residual life plot for our precipitation data.

Deep Set Link to heading

To accommodate the variable size set of excess values as input predictor, $x_{i l}^{s}$, we employ a deep set architecture to transform the variable-length input into fixed size vector. The transformation consists of the following two stages.

The first stage is responsible for transforming each element of the set, $x_{i l, j}^{s}$, from its raw representation into a high-level vector representation, $h_{i l, j}$ by using a fully connected network, $\phi$. These element-wise representations are then aggregated to obtain a fixed-length vector representation for the set.

This set-level representation is then used as input to a fully connected network, $\rho$, to produce the final output representation, $z_{i l}^{s}=\rho\left[\sum_{j} \phi\left(x_{i l, j}^{s}\right)\right]$

DeeGPD Framework Link to heading

- Local Feature Extraction - This component is responsible for transforming both the (fixed-length) vectorvalued, $x_{i l}^{v}$, and (variable-length) set-valued predictors, $x_{i l}^{s}$, at each location into a fixed-length feature vector.

- Spatial Feature Extraction - This component models the spatial relationships among the predictors in the data.

- Extreme Value Modeling (EVM) - This component is responsible for ensuring that the constraints on the GPD parameters are satisfied by the induced model.

Local Feature Extraction Link to heading

Learning a representation of the predictors is challenging for two reasons. First, because the set-valued predictors are variable length the authors must transform them into a fixed length vector so that it can be used by the later stages of the model. Second, the set-valued predictors may not always be available for some locations.

To address the first challenge, the authors employ the deep set architecture described in subsection to transform the set-valued predictors into a fixed-length vector, $z_{i l}^{s}$.

For the second challenge, there may be some cases where a given grid cell lacks set-valued predictors, $x_{i l}^{s}$. In these cases the authors set $z_{i l}^{s}=0$. However, zeroing the inputs in this way risks the possibility that predictions at locations without set predictors will be distorted. To address this, an indicator variable, $I_{i l}$ is introduced to indicate whether set-valued predictors are available at a given location and time. This indicator variable is then concatenated with the vector-valued predictors and the deep set representation of the set-valued predictors to generate the following vector: $z_{i l}=z_{i l}^{s}\left|I_{i l}\right| x_{i l}^{v}$, where $|$ denotes the concatenation operator.

After each set element is processed by several fully connected layers, only the representations of the actual set elements (i.e. dummy elements excluded) are averaged together. This is implemented through the use of a masking array multiplied by the set member representations element-wise.

Spatial Feature Extraction Link to heading

After extracting a separate representation for each location, the authors need to model the spatial relationships between the representations at different locations. DeepGPD uses a CNN to capture the geospatial relationships in the data. The authors arrange the representation extracted from all the gridded locations into a $3$-dimensional tensor (excluding the batch dimension) and then provide the tensor as input to a CNN with residual layers. The final linear layer of the CNN produces a response map for each location, $k_{i l} \in \mathbb{R}^{2}$, for the prediction time window $\left(t_{i}, t_{i+1}\right]$.

Extreme Value Modeling (EVM) Link to heading

The EVM component is designed to predict the conditional distribution of excess values by utilizing the response map generated by the CNN. Specifically, it will convert the CNN output for each location and time window $\left(t_{i}, t_{i+1}\right]$ to the generalized Pareto model parameters, $\xi_{i l}$ and $\sigma_{i l}$. These parameters enable us to infer various statistics about the excess values in the predicted time window, such as the expected values at varying quantiles (including maximum and median value) as well as their return level.

DeepGPD enables both parameters to be automatically learned from the data. Specifically, the deep architecture is trained to minimize the following negative loglikelihood function of the excess values in the next time step:

$$ \mathcal{L}\left(\left\{\xi_{i l}, \sigma_{i l}\right\}\right)=\sum_{i, l, j}\left[\log \sigma_{i l}+\left(1+\frac{1}{\xi_{i l}}\right) \log \left(1+\xi_{i l} \frac{y_{i l j}}{\sigma_{i l}}\right)\right] \tag{4} $$One major computational challenge in estimating the GPD parameters using a deep learning architecture is the need to enforce positivity constraints on the solution of (4) during training. To address this challenge, DeepGPD employs a re-parameterization trick to transform $\left(\xi_{i l}, \sigma_{i l}\right)$ into a pair of unconstrained variables $k_{i l}=\left(k_{i l}^{(1)}, k_{i l}^{(2)}\right)$ that can be learned by the convolutional neural network.

Let \(\left\{\xi_{i l}^{*}, \sigma_{i l}^{*}\right\}=\operatorname{argmin} \mathcal{L}\left(\left\{\xi_{i l}, \sigma_{i l}\right\}\right)\) subject to the following positivity constraints:

$$ \forall i, j, l: \sigma_{i l}>0 \text { and } 1+\xi_{i l} \frac{y_{i l j}}{\sigma_{i l}}>0 $$By re-parameterizing $\left(\xi_{i l}, \sigma_{i l}\right) \mapsto\left(k_{i l}^{(1)}, k_{i l}^{(2)}\right)$ as follows:

$$ \sigma_{i l}=\exp \left(k_{i l}^{(1)}\right), \quad \xi_{i l}=\exp \left(k_{i l}^{(2)}\right)-\frac{\exp \left(k_{i l}^{(1)}\right)}{M_{i l}} \tag{5} $$and solving for \(\left\{\hat{k}_{i l}^{(1)}, \hat{k}_{i l}^{(2)}\right\}=\operatorname{argmin} \hat{\mathcal{L}}\left(\left\{u_{i l}, v_{i l}\right\}\right)\), where

$$ \hat{\mathcal{L}}\left(\left\{u_{i l}, v_{i l}\right\}\right)=\sum_{i l j}\left[u_{i l}+\left(1+\frac{M_{i l}}{M_{i l} e^{v_{i l}}-e^{u_{i l}}}\right)\times \log \left(1+e^{v_{i l}} \frac{y_{i l j}}{e^{u_{i l}}}-\frac{y_{i l j}}{M_{i l}}\right)\right] \tag{6} $$and $M_{i l}=\max_{j} Y_{i l j}$, then the solution set \(\left\{\xi_{i l}^{*}, \sigma_{i l}^{*}\right\}\) can be derived from the solution for \(\left\{\hat{k}_{i l}^{(1)}, \hat{k}_{i l}^{(1)}\right\}\) by applying the mapping given in Equation (5).

The proof for the preceding theorem can be shown by substituting (5) into (4), which yields the equivalent objective function for \(\hat{\mathcal{L}}\left(\left\{k_{il}^{(1)}, k_{il}^{(2)}\right\}\right)\). Furthermore, since Equation (4) can be re-written as follows:

$$ \sigma_{i l} =e^{k_{i l}^{(1)}} \geq 0 $$$$ 1+\xi_{i l} \frac{y_{i l j}}{\sigma_{i l}} =1-\frac{y_{i l j}}{M_{i l}}+e^{k_{i l}^{(2)}} \frac{y_{i l j}}{e^{k_{i l}^{(1)}}} \geq 0 $$the positivity constraints are automatically satisfied given the fact that $\forall i, l, j: y_{i l j} \leq M_{i l}, e^{k_{i l}^{(1)}}>0$ and $e^{k_{i l}^{(2)}}>0$ as long as $k_{i l}^{(1)}$ and $k_{i l}^{(2)}$ are not equal to $-\infty$.

The DeepGPD framework trained to optimize the loss function in Equation (6) will generate the maximum likelihood solution for \(\left\{\xi_{i l}^{*}, \sigma_{i l}^{*}\right\}\) in Equation (4) given the one-to-one mapping with \(\left\{\hat{k}_{i l}^{(1)}, \hat{k}_{i l}^{(2)}\right\}\) in Equation (5).

\(\left\{\xi_{i l}^{*}\right. and \left.\sigma_{i l}^{*}\right\}\). This enables the parameters to be more easily learned by DeepGPD. All three components of the framework, including deep set and CNN, are trained in an endto-end fashion using Adam. Once the parameters for \(\hat{k}_{i l}^{(1)}\) and \(\hat{k}_{i l}^{(2)}\) are obtained, we can apply Equation (5) to derive the corresponding GPD parameters.