Abstract Link to heading

Classification of time series data is an important task for many application domains. One of the best existing methods for this task, in terms of accuracy and computation time, is MiniROCKET. In this work, we extend this approach to provide better global temporal encodings using hyperdimensional computing (HDC) mechanisms. HDC (also known as Vector Symbolic Architectures, VSA) is a general method to explicitly represent and process information in high-dimensional vectors. It has previously been used successfully in combination with deep neural networks and other signal processing algorithms. We argue that the internal high-dimensional representation of MiniROCKET is well suited to be complemented by the algebra of HDC. This leads to a more general formulation, HDC-MiniROCKET, where the original algorithm is only a special case. We will discuss and demonstrate that HDC-MiniROCKET can systematically overcome catastrophic failures of MiniROCKET on simple synthetic datasets. These results are confirmed by experiments on the 128 datasets from the UCR time series classification benchmark. The extension with HDC can achieve considerably better results on datasets with high temporal dependence without increasing the computational effort for inference.

Introduction Link to heading

MiniROCKET applies a set of parallel convolutions to the input signal. To achieve a low runtime, two important design decisions of MiniROCKET are (1) the usage of convolution filters of small size and (2) accumulation of filter responses over time based on the Proportion of Positive Values (PPV), which is a special kind of averaging. However, the combination of these design decisions can hamper the encoding of temporal variation of signals on a larger scale than the size of the convolution filters. To address this, the authors of MiniROCKET propose to use dilated convolutions. A dilated convolution virtually increases a filter kernel by adding sequences of zeros in between the values of the original filter kernel [12] (e.g. \([-1, 2, 1]\) becomes \([-1, 0, 2, 0 1]\) or \([-1, 0, 0, 2, 0, 0, 1]\) and so on).

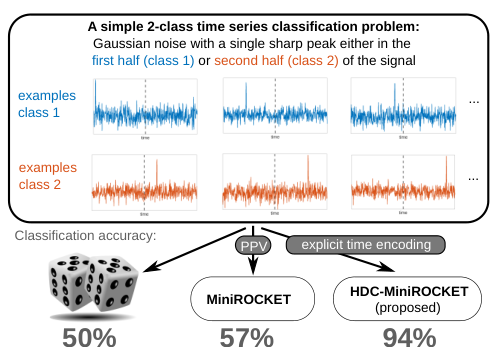

The first contribution of this paper is to demonstrate that although the dilatated convolutions of MiniROCKET perform well on a series of standard benchmark datasets like UCR [13], it is easy to create datasets where classification based on MiniROCKET is not much better than random guessing. This is due to a combination of two problems: (1) The location of the sharp peaks cannot be well captured by dilated convolutions with high dilation values due to their large gaps. (2) Although responses of filters with small or no dilation can represent the peak, the averaging implemented by PPV removes the temporal information on the global scale.

HDC-MiniROCKET, that addressed this second problem. It is based on the observation that MiniROCKET’s Proportion of Positive Values (the second design decision from above) is a special case of a broader class of accumulation operations known as bundling in the context of Hyperdimensional Computing (HDC) and Vector Symbolic Architectures (VSA) [14]–[17]. This novel perspective encourages a straight-forward and computational efficient usage of a second HDC operator, binding, in order to explicitly and flexibly encode temporal information during the accumulation process in MiniROCKET. The original MiniROCKET then becomes a special case of the proposed more general HDC-MiniROCKET.

Related Work Link to heading

Time Series Classification Link to heading

The survey papers used dataset collections for benchmarking: 1) the University of California, Riverside (UCR) time series classification and clustering repository [13] for univariate time series, and 2) the University of East Anglia (UEA) repository [19] for multivariate time series.

ROCKET and MiniROCKET Link to heading

As said before, MiniROCKET [9] is a variant of the earlier ROCKET [8] algorithm. Based on the great success of convolutional neural networks, both variants build upon convolutions with multiple kernels. However, learning the kernels is difficult if the dataset is too small, so [8] uses a fixed set of predefined kernels. While ROCKET uses randomly selected kernels with a high variety on length, weights, biases and dilations, MiniROCKET is more deterministic. It uses predefined kernels based on empirical observations of the behavior of ROCKET. Furthermore, instead of using two global pooling operation in ROCKET (max-pooling and proportion of positive values, PPV), MiniROCKET uses just one pooling value – the PPV. This leads to vectors that are only half as large (about \(10,000\) instead of \(20,000\) dimensions). MiniROCKET is up to \(75\) times faster than ROCKET on large datasets. To classify feature vectors, both ROCKET and MiniROCKET use a simple ridge regression.

Hyperdimensional Computing (HDC) Link to heading

Hyperdimensional computing (also known as Vector Symbolic Architectures, VSA) is an established approach to solve computational problems using large numerical vectors (hypervectors) and well-defined mathematical operations. Basic literature with theoretical background and details on implementations of HDC are [14]–[17]; further general comparisons and overviews can be found in [22]–[25]. Moreover, hypervectors are also intermediate representations in most artificial neural networks. Therefore, a combination with HDC can be straightforward. Related to time series, for example, [30] used HDC in combination with deep-learned descriptors for temporal sequence encoding for image-based localization. A combination of HDC and neural networks for multivariate time series classification of driving styles was demonstrated in [37]. There, the HDC approach was used to first encode the sensory values and to then combine the temporal and spatial context in a single representation. This led to faster learning and better classification accuracy compared to standard LSTM neural networks.

Methodology Link to heading

MiniROCKET Link to heading

Input is a time series signal \(x \in \mathbb{R}^T\) where \(T\) is the length of the time series. MiniROCKET can compute a \(D = 9,996\) dimensional output vector \(y\) that describes this signal.

The first step in MiniROCKET is a dilated convolution of the input signal \(x\) with kernels \(W_{k,d}\):

$$ c_{k,d} = x \star W_{k,d} $$$d$ is the dilation parameter, \(k \in \{1, \ldots, 84\}\) refers to \(84\) predefined kernels \(W_k\). The length and weights of these kernels are based on insights from the first ROCKET method [8]: the MiniROCKET kernels have a length of \(9\), the weights are restricted to one of two values \(\{-1, 2\}\), and there are exactly three weights with value \(2\).

In a second step, each convolution result \(c_{k,d}\) is element-wise compared to one or multiple bias values \(B_b\)

$$ c_{k,d,b} = c_{k,d} > B_b $$This is an approximation of the cumulative distribution function of the filter responses of this particular combination of kernel $k$ and dilation $d$.

The final step of MiniROCKET is to compute each of the \(9,996\) dimensions of the output descriptor \(y^{PPV}\) as the mean value of one of the \(c_{k,d,b}\) vectors (referred to as PPV in [9]). This averaging is where potentially important temporal information is lost and this final step will be different in HDC-MiniROCKET.

HDC-MiniROCKET Link to heading

The important difference is that HDC-MiniROCKET uses a Hyperdimensional Computing (HDC) binding operator to bind the convolution results to timestamps before creation of the final output.

A HDC perspective on MiniROCKET Link to heading

One of these operations is bundling \(\oplus\). Input to the bundling operation are two or more vectors from a vector space V and the output is a vector of the same size that is similar to each input vector. Dependent on the underlying vector space \(\mathbb{V}\), there are different Vector Symbolic Architectures (VSAs) that implement this operation differently. For example, the multiply-add-permute (MAP) architecture [16] can operate on bipolar vectors (with values \(\{-1, 1\}\)) and implements bundling with a simple element-wise summation – in high-dimensional vector spaces, the sum of vectors is similar to each summand [15]

The valuable connection between HDC and MiniROCKET is that the \(9,996\) different vectors \(c_{k,d,b} \in \{0, 1\}^T\) from Eq. 2 in MiniROCKET also constitute a \(9,996\)-dimensional feature vector \(F_t\) for each timestep \(t \in \{1,\ldots,T\}\) (think of each vector \(c_{k,d,b}\) being a row in a matrix, then these feature vectors \(F_t\) are the columns). The averaging in MiniROCKET’s PPV (i.e. the row-wise mean in the above matrix) is then equivalent to bundling of these vectors \(F_t\). More specifically, if we convert \(F_t\) to bipolar by \(F_{t}^{BP} = 1 - 2 F_{t}\) and use the MAP architecture’s bundling operation (i.e. elementwise addition) then the result is proportional to the output of MiniROCKET:

$$ \bigoplus_{t=1}^{T}F_{t}^{B P}=\sum_{t=1}^{T}(1-2F_{t})\propto y_{PPV} $$This is just another way to compute output vectors that point in the same directions as the MiniROCKET output – which preserves cosine similarities between vectors. But much more importantly, it encourages the integration of a second HDC operation, binding \(\otimes\), as described in the following section.

HDC-MiniROCKET extends MiniROCKET by using the HDC binding \(\otimes\) operation to also encode the timestamp \(t\) of each feature \(F_t^{BP}\) in the output vector (without increasing the vector size).

$$ $y^{H D C}=\bigoplus_{t=1}^{T}(F_{t}^{B P}\otimes P_{t})=\sum_{t=1}^{T}(1-2F_{t}) \odot P_{t} $$